- Department of Physics

- Observatory

- PHYS 162H Honors Project

- Luna: Our Moon

Luna: Our Moon

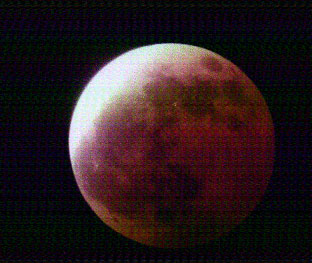

Our Satellite, the Moon, has a vast array of mysteries associated with it. It has always held a sense of awe and mystery to living things on the planet Earth, from wolves baying at its rising, to humans watching with telescopes. Its cratered and battered surface provide great clues regarding our own history, as well as the history of the solar system. The Moon also holds significance as the first step of Man (hopefully not the last) off of this world.

Our Satellite, the Moon, has a vast array of mysteries associated with it. It has always held a sense of awe and mystery to living things on the planet Earth, from wolves baying at its rising, to humans watching with telescopes. Its cratered and battered surface provide great clues regarding our own history, as well as the history of the solar system. The Moon also holds significance as the first step of Man (hopefully not the last) off of this world.

One of the dominant features of the moon is its craters. The focus of many observations of the moon involve examining the patch-work of craters overlapping and covering the surface. The moon is subjected to intense bombardment by small asteroids and similar debris in our system but, unlike the Earth, it has no atmosphere to protect it. Careful examination of the moon's craters will reveal several generations of craters with older ones overlapped by younger ones. Some of the craters will have scattered ejecta radiating from them.

Another fascinating and easily observable feature of the moon is the maria or lunar lowlands. They appear darker and smoother than the rest of the surface of the moon facing us, so much so that early Italian astronomers were compelled to call them mare, or seas. The remainder of the surface is the cratered and mountainous highlands or terrae. The Mare are composed of basalt for the most part, hence their darker color.

A project centered upon the moon is observationally the easiest, but photographically difficult. You will want high quality images to use for your calculations, which will require a little finesse with the camera.

Procedure

Locate the Moon in the telescope at Davis Hall.

With the observatory manager's assistance, attach either a camera or the CCD to the scope. Sketching craters could be fun for the artistically inclined.

Capture at least one image, or more if you choose. Try several different images in different scopes and powers of magnification. Choose which image gives the sharpest definition of the craters and moon shadows of the mountains. Images of Mare are also of interest concerning the structure of the moon. Try to capture an image of an overlapped crater network and a crater with a raised center.

With use of photography, or with the CCD images, the pictures may be enlarged so that shadows and features may be more visible. Once you have collected a wide variety of data, you may procede to the interpretations below.

Measurements With The Craters

Using geometry, it is possible to estimate the depth of a crater fairly accurately by the shadows in the craters. The TA will show you how to do this. You can also estimate the diameter of craters by the size of them in relation to the size of the Moon. Use the Moon's diameter to calculate a visible surface area. This works best on craters that are "dead on" to the viewer.

Mare and Lunar Geological Activity

Mare are areas of dense basaltic material, suggesting that at some point liquid rock lava flowed over the surface of the moon. In some places, craters have only been partially filled by the magmatic substance, and a few pictures of this will aid in any claim you might make as to the age of the craters and geological activity on the Moon. The Moon is a dead world, but it could be liquified by, say, an asteroid of sufficient size.

Observing The Phases of The Moon

Also of observational use is to observe the moon through one complete cycle of its phases. This does not entail going to the observatory as much as simply going outside and recording the phase the moon is in that night. In one month you will see the full range of phases. If you pursue this, be sure to include discussion on why we see the moon in different phases. Also discuss why we always see the same side of the moon. Determine how long it takes to go through one lunar cycle.

Observatory Manager

Jeremy Benson

jjbenson@niu.edu

Location

Davis Hall Room 703Normal and Locust Roads

DeKalb, IL 60115Google Maps